A norm is any uniform attitude or action that two or more people share by virtue of their membership in a group. We experience our attitudes toward productivity as private and personal, as originating in our own thinking, experience, and motivation, and as unique to each of us. What we fail to realize is that our attitudes arise from the norms of the groups in which we hold memberships. As a result, group norms for productivity and our attitudes toward them regulate a greater part of our work effort or lack of it than we realize.

Norms are the most powerful silent catalyst in teams. They draw a line in the sand between being a member and being an outsider. Norms define a team’s culture and dictate what behaviors are acceptable and unacceptable. Norms are not necessarily written in policy manuals, but every team member has a vivid understanding of them.

To get an understanding of your own team norms, imagine that you have been assigned to orient a new team member to routine team operations. Think about your team norms and all the issues you would have to cover with an outsider who knows nothing about your team. Some examples of statements that indicate norms are:

“I know the policy says that, but we do it this way.”

“Stay away from that person (or group). You don’t want to be associated too closely with them.”

“It may seem unusual, but that’s the way we do it.”

“Policy says these reports need to be done weekly, but we probably only do them once a month. No one pays any attention to them anyway.”

We conduct meetings like this…”

Norms are the silent and powerful forces that direct and guide behavior. They are not good or bad, but a simple fact of life. In other words, norms are like a landscape. Sound norms are the blossoms that enhance team performance. Unsound norms are weeds that, when left unchecked, hinder team performance. Given that, teams and leaders need to understand how to create sound norms or change existing unsound norms into ones that inspire excellence in teamwork and performance.

Norms are the building blocks for a company’s culture. To illustrate how norms work to shape a culture, picture two aquariums side by side. Both aquariums look identical from the outside. They seem to have the same variety of fish, plants, water, food, etc. When you look closer, however, one aquarium has the perfect number of fish, the ideal amount of food, and the best balance of plant life, along with the right temperature and light. The aquarium has a healthy culture. The fish and plant life thrive with energy and health.

The other aquarium appears the same from the outside but its temperature is off by a couple of degrees. The plant life is a little out of balance. There are a few too many fish, and not quite enough food. The aquarium has an unhealthy culture. The fish and plant life struggle to survive.

If you take a fish from the unhealthy aquarium and put it into the healthy aquarium, the fish will begin to improve and, over time, become invigorated with new, vibrant energy and color. Conversely, if you take a fish from the healthy aquarium and put it into the unhealthy aquarium, that fish begins to adapt to the conditions of the unhealthy environment. Colors fade, it becomes sluggish and disoriented.

Now picture a row of corporate office buildings, all looking strong, powerful, and healthy from the outside. The same principle applies as with the aquarium when introducing new people into an established culture.

Group Dynamics: How Norms Form

Leaders are the captives of their cultures. Choices remain unseen because those responsible for change are surrounded by the mirrors of the very culture they have created.

– Drs. Robert R. Blake and Jane S. Mouton

Group dynamics can make or break a change effort. They are the silent drivers and primary source for change that either encourage or impede momentum. Norms develop through three basic laws of human behavior demonstrated through relationships, teams, and organizations:

Convergence

Cohesion

Conformity

In the same way that comprehending the law of gravity helps to understand the behavior of objects, comprehending the basic laws of group dynamics helps in understanding the power of norms and their influence on behavior and performance. Moreover, there is a natural source of power in these dynamics that a skilled and knowledgeable team can harness for maximum effectiveness.

People think of values and attitudes as private, personal, and unique, but research shows that most personal attitudes arise from group norms. As a result, team attitudes determine the quality of individual work effort more than most people realize. The norms of a group are reflected in its traditions, precedents, habits, rites, rules, rituals, regulations, policies, operating procedures, customs, taboos, and past practices. These norms begin forming through a process known as convergence.

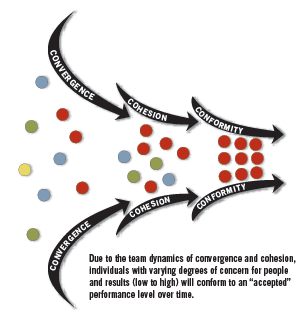

Convergence

Convergence initiates norms spontaneously by shifting individual attitudes or patterns of behavior toward a uniform group pattern that every member shares. Few social pressures are more important for understanding change than the human tendency to converge around a common idea in a group setting. For example: a team has several members, each of whom starts out a planning meeting with an opinion regarding how much productivity is “enough.” One person thinks fifteen “units” per day is adequate, another recommends only five, while other members suggest thirteen, nine, or eight, etc. As people work together and exchange ideas, the opinions expressed lead to a shift in attitudes around a more uniform norm. Research has shown that this common dilemma is almost always resolved by a common convergence to the middle position. In the illustration, the agreed-upon productivity benchmark becomes ten, or close to ten.

Group dynamics: convergence, cohesion, conformity.

Cohesion

Cohesion is the phenomenon by which people in groups congregate around common interests and values. People prefer to associate with other people like them and by whom they are liked. Cohesion is one of the most significant forces for social organization. People are naturally drawn to others who share a common experience that allows them to bypass the formalities they follow with outsiders. Examples of cohesion surface in every aspect of life as people tend to gravitate toward and give preference to others who share common interests or experiences. This preference may follow the lines of race, gender, religion, politics, socioeconomic status, or education. In organization life, other dimensions apply, such as years of service, position, level of training, or common work experience.

Cohesion is the emotional attraction people feel toward one another, and as such it accelerates the development of norms. On a social basis, we call this “bonding.” When cohesion is strong, people relate to each other with a stronger sense of trust, confidence, and commitment. They embrace the norms with pride because the shared experience feels comfortable and right. Cohesion is demonstrated in comments like, “We’ll do whatever it takes to make this happen.”

Conformity

Once a norm is established, conformity is the natural force that influences group members to maintain that norm. Conformity enforces the norm by creating pressure, often subtly, to “fall in line” with the group in reinforcing the norm. Conformity happens every time a co-worker says, “I know it’s a little unusual, but we don’t use a formal agenda for these meetings,” or “You’re coming across too strong in meetings. We like to keep these meetings relaxed and spontaneous.” The message, whether given by a gesture, comment, or outright directive, is “You need to change your behavior to fit in.” The price of non-conformity is rejection.

The Impact of Norms on the Organization and Team

Only through a never-ending effort to override the automatic behavior of the past could a change in relationships even be a remote possibility.

– Dr. Robert R. Blake

Once the dynamics are understood, the key question for every organization is “Are we conforming to norms that help us or hinder us?” In the same way that individuals can become aware of individual behavior and its impact on others, teams and entire organizations can become aware of their norms and the impact on results.

Like norms themselves, the laws of convergence, cohesion, and conformity are neither good nor bad, but are dynamics that simply happen. The influence they wield can bring power to an organization that chooses to understand and lead these norms. Left alone, they can evolve into norms that may devastate a company’s fortunes because leaders are looking elsewhere (the economy, government, or competition) for causes of poor performance. Like other natural laws, group dynamics operate 24 hours a day, rain or shine, profit or loss, in every organization. Ineffective norms have a way of creeping up unnoticed like weeds in a garden, hampering an organization’s efforts to change. To avoid this, successful organizations prevent the weeds from growing by constantly challenging unsound norms and continually reinforcing sound ones.

In Good to Great, Jim Collins compares the executive culture of two steel industry companies, Bethlehem Steel and Nucor. Both companies faced devastating setbacks in the 1980s due to a recession and the competitive challenge of cheap, imported steel. Bethlehem Steel reacted with deep cuts throughout the organization, while at the same time constructing a 21-story office building to house its executive staff. At extra expense, it designed the building in the shape of a cross in order to accommodate the large number of vice presidents who needed corner offices. Other norms for executives included using the corporate jets for weekend getaways. There were also executive golf memberships, and rank even determined shower priority at these clubs. Collins says, “Bethlehem did not decline in the 1970s and 1980s primarily because of imports or technology—Bethlehem declined first and foremost because it was a culture wherein people focused their efforts on negotiating the nuances of an intricate social hierarchy, not on customers, competitors, or changes in the external world.” Unsound norms were so strong as to manage the organization instead of the organization managing its norms.

At the other side of the spectrum was Nucor, which at the same time “took extraordinary steps to keep at bay the class distinctions that eventually encroach on most organizations.” Facing the same industry conditions, executives did not receive better benefits than front-line workers. In fact, executives had fewer perks. For example, all workers (but not executives) were eligible to receive $2,000 per year per child for up to four years of post-high school education. When Nucor had a profitable year, everyone in the company benefited. When Nucor faced tough times, everyone from the top to the bottom suffered. But people from the top suffered more. In a recent recession, for example, worker pay went down 25 percent, officer pay went down 50 percent, and the CEO’s pay went down 75 percent.

Companies that never challenge unsound norms or reinforce sound norms can find themselves at a severe disadvantage when trying to compete. A simple norm like executive perks may seem minor, but it communicates a powerful message to non-executives throughout an organization that undermines commitment and a sense of personal stake.

Changing Norms

It is only when we examine the extent to which personal attitudes, thoughts, and feelings are shared with primary group members that the regulating effect of informal norms and standards become clearly visible.

– Drs. Robert R. Blake and Jane S. Mouton

A chaos of conflicting, reluctant, and confused responses develops every time a change is introduced. This chaos creates the first stage of convergence and conformity. This stage provides teams with a critical opportunity to influence change because within the confusion lies valuable potential for leadership, creativity, and standards of excellence. This is where the “how much is enough” question is being asked and tested, when norms are in their early stages. At this pivotal point, when the group is beginning to form new norms, a leader’s style can influence how the group converges.

It is essential for leaders to be aware that these three valuable sources of energy—convergence, cohesion, and conformity—exist during periods of change. Learning how to harness them productively makes the difference between developing sound or unsound norms. There is little as demotivating to people as leadership that continues to ignore obvious realities and continues with ineffective strategies because it cannot or will not face reality.

In Good to Great, Jim Collins described the following quality as being a key factor in all “Good to Great” companies:

“On the one hand, they (‘good to great’ companies) stoically accepted the brutal facts of reality. On the other hand, they maintained an unwavering faith in the endgame, and a commitment to prevail as a great company despite the brutal facts.”

Companies that succeed in staying on the cutting edge of competition all have one thing in common: they question everything and constantly challenge norms so that complacency never sets in. Unless they are challenged, norms can become outmoded, ineffective, and deeply entrenched in the culture. When this occurs, companies perpetuate unsound practices because “That’s the way we do it around here,” even when better ways are available.

Setting Soundest Norms for Team Development

Teams establish sound norms by examining the effectiveness of existing norms. Conditions required for setting sound team standards include:

Involvement: Those who will be guided by the standards participate in establishing them.

Clarity: The standards are realistic and clearly defined.

Challenge: The standards inspire and motivate team members to achieve new levels of performance. If they do not challenge people, business will simply continue as usual and the standard-setting exercise will have been in vain.

Understanding: Every team member fully understands the meaning of each standard.

Commitment: Team members resolve to perform by the standards they set for themselves.

Excellence: Team members agree on what constitutes excellent performance and adopt standards to foster such excellence.

At Grid International, we work with clients to help them maximize their human capital. Every strategy is different and every challenge unique, but the patterns of group dynamics and culture are universal and absolutely critical for gaining a performance edge. Having a clear understanding of the group dynamics of culture and how they work is essential for mobilizing both small and large groups of people. All change efforts must begin by understanding the existing culture and how to manage and maximize this invaluable resource. We give clients the power to develop cultures that constantly reinforce standards of excellence. For more information on how you can understand and harness norms for positive and enduring transformation,