CEOs and senior executives can employ proven techniques to create top-team performance.

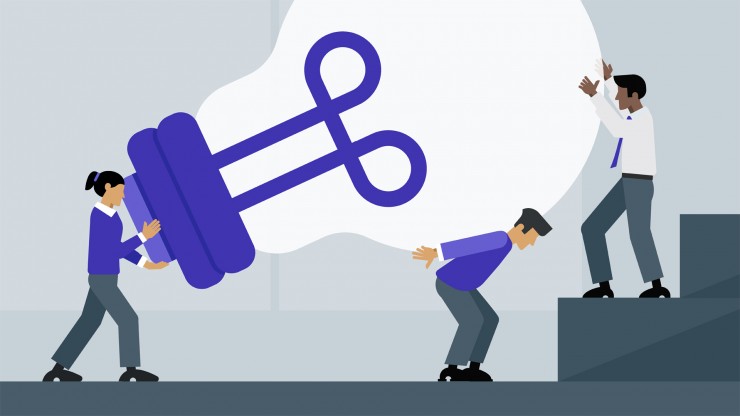

The value of a high-performing team has long been recognized. It’s why savvy investors in start-ups often value the quality of the team and the interaction of the founding members more than the idea itself. It’s why 90 percent of investors think the quality of the management team is the single most important nonfinancial factor when evaluating an IPO. And it’s why there is a 1.9 times increased likelihood of having above-median financial performance when the top team is working together toward a common vision.1“No matter how brilliant your mind or strategy, if you’re playing a solo game, you’ll always lose out to a team,” is the way Reid Hoffman, LinkedIn cofounder, sums it up. Basketball legend Michael Jordan slam dunks the same point: “Talent wins games, but teamwork and intelligence win championships.”

The topic’s importance is not about to diminish as digital technology reshapes the notion of the workplace and how work gets done. On the contrary, the leadership role becomes increasingly demanding as more work is conducted remotely, traditional company boundaries become more porous, freelancers more commonplace, and partnerships more necessary. And while technology will solve a number of the resulting operational issues, technological capabilities soon become commoditized.

Building a team remains as tough as ever. Energetic, ambitious, and capable people are always a plus, but they often represent different functions, products, lines of business, or geographies and can vie for influence, resources, and promotion. Not surprisingly then, top-team performance is a timeless business preoccupation. (See sidebar “Cutting through the clutter of management advice,” which lists top-team performance as one of the top ten business topics of the past 40 years, as discussed in our book, Leading Organizations: Ten Timeless Truths.)

Amid the myriad sources of advice on how to build a top team, here are some ideas around team composition and team dynamics that, in our experience, have long proved their worth.

Team composition

Team composition is the starting point. The team needs to be kept small—but not too small—and it’s important that the structure of the organization doesn’t dictate the team’s membership. A small top team—fewer than six, say—is likely to result in poorer decisions because of a lack of diversity, and slower decision making because of a lack of bandwidth. A small team also hampers succession planning, as there are fewer people to choose from and arguably more internal competition. Research also suggests that the team’s effectiveness starts to diminish if there are more than ten people on it. Sub-teams start to form, encouraging divisive behavior. Although a congenial, “here for the team” face is presented in team meetings, outside of them there will likely be much maneuvering. Bigger teams also undermine ownership of group decisions, as there isn’t time for everyone to be heard.

Stay current on your favorite topics

SUBSCRIBE

Beyond team size, CEOs should consider what complementary skills and attitudes each team member brings to the table. Do they recognize the improvement opportunities? Do they feel accountable for the entire company’s success, not just their own business area? Do they have the energy to persevere if the going gets tough? Are they good role models? When CEOs ask these questions, they often realize how they’ve allowed themselves to be held hostage by individual stars who aren’t team players, how they’ve become overly inclusive to avoid conflict, or how they’ve been saddled with team members who once were good enough but now don’t make the grade. Slighting some senior executives who aren’t selected may be unavoidable if the goal is better, faster decisions, executed with commitment.

Of course, large organizations often can’t limit the top team to just ten or fewer members. There is too much complexity to manage and too much work to be done. The CEO of a global insurance company found himself with 18 direct reports spread around the globe who, on their videoconference meetings, could rarely discuss any single subject for more than 30 minutes because of the size of the agenda. He therefore formed three top teams, one that focused on strategy and the long-term health of the company, another that handled shorter-term performance and operational issues, and a third that tended to a number of governance, policy, and people-related issues. Some executives, including the CEO, sat on each. Others were only on one. And some team members chosen weren’t even direct reports but from the next level of management down, as the CEO recognized the importance of having the right expertise in the room, introducing new people with new ideas, and coaching the next generation of leaders.

Team dynamics

It’s one thing to get the right team composition. But only when people start working together does the character of the team itself begin to be revealed, shaped by team dynamics that enable it to achieve either great things or, more commonly, mediocrity.

Consider the 1992 roster of the US men’s Olympic basketball team, which had some of the greatest players in the history of the sport, among them Charles Barkley, Larry Bird, Patrick Ewing, Magic Johnson, Michael Jordan, Karl Malone, and Scottie Pippen. Merely bringing together these players didn’t guarantee success. During their first month of practice, indeed, the “Dream Team” lost to a group of college players by eight points in a scrimmage. “We didn’t know how to play with each other,” Scottie Pippen said after the defeat. They adjusted, and the rest is history. The team not only won the 1992 Olympic gold but also dominated the competition, scoring over 100 points in every game.

What is it that makes the difference between a team of all stars and an all-star team? Over the past decade, we’ve asked more than 5,000 executives to think about their “peak experience” as a team member and to write down the word or words that describe that environment. The results are remarkably consistent and reveal three key dimensions of great teamwork. The first is alignment on direction, where there is a shared belief about what the company is striving toward and the role of the team in getting there. The second is high-quality interaction, characterized by trust, open communication, and a willingness to embrace conflict. The third is a strong sense of renewal, meaning an environment in which team members are energized because they feel they can take risks, innovate, learn from outside ideas, and achieve something that matters—often against the odds.

So the next question is, how can you re-create these same conditions in every top team?

Getting started

The starting point is to gauge where the team stands on these three dimensions, typically through a combination of surveys and interviews with the team, those who report to it, and other relevant stakeholders. Such objectivity is critical because team members often fail to recognize the role they themselves might be playing in a dysfunctional team.

While some teams have more work to do than others, most will benefit from a program that purposefully mixes offsite workshops with on-the-job practice. Offsite workshops typically take place over two or more days. They build the team first by doing real work together and making important business decisions, then taking the time to reflect on team dynamics.

The choice of which problems to tackle is important. One of the most common complaints voiced by members of low-performing teams is that too much time is spent in meetings. In our experience, however, the real issue is not the time but the content of meetings. Top-team meetings should address only those topics that need the team’s collective, cross-boundary expertise, such as corporate strategy, enterprise-resource allocation, or how to capture synergies across business units. They need to steer clear of anything that can be handled by individual businesses or functions, not only to use the top team’s time well but to foster a sense of purpose too.

The reflective sessions concentrate not on the business problem per se, but on how the team worked together to address it. For example, did team members feel aligned on what they were trying to achieve? Did they feel excited about the conclusions reached? If not, why? Did they feel as if they brought out the best in one another? Trust deepens regardless of the answers. It is the openness that matters. Team members often become aware of the unintended consequences of their behavior. And appreciation builds of each team member’s value to the team, and of how diversity of opinion need not end in conflict. Rather, it can lead to better decisions.

Many teams benefit from having an impartial observer in their initial sessions to help identify and improve team dynamics. An observer can, for example, point out when discussion in the working session strays into low-value territory. We’ve seen top teams spend more time deciding what should be served for breakfast at an upcoming conference than the real substance of the agenda (see sidebar “The ‘bike-shed effect,’ a common pitfall for team effectiveness”). One CEO, speaking for five times longer than other team members, was shocked to be told he was blocking discussion. And one team of nine that professed to being aligned with the company’s top 3 priorities listed no fewer than 15 between them when challenged to write them down.

Back in the office

Periodic offsite sessions will not permanently reset a team’s dynamics. Rather, they help build the mind-sets and habits that team members need to first observe then to regulate their behavior when back in the office. Committing to a handful of practices can help. For example, one Latin American mining company we know agreed to the following:

- A “yellow card,” which everyone carried and which could be produced to safely call out one another on unproductive behavior and provide constructive feedback, for example, if someone was putting the needs of his or her business unit over those of the company, or if dialogue was being shut down. Some team members feared the system would become annoying, but soon recognized its power to check unhelpful behavior.

- An electronic polling system during discussions to gauge the pulse of the room efficiently (or, as one team member put it, “to let us all speak at once”), and to avoid group thinking. It also proved useful in halting overly detailed conversations and refocusing the group on the decision at hand.

- A rule that no more than three PowerPoint slides could be shared in the room so as to maximize discussion time. (Brief pre-reads were permitted.)

After a few months of consciously practicing the new behavior in the workplace, a team typically reconvenes offsite to hold another round of work and reflection sessions. The format and content will differ depending on progress made. For example, one North American industrial company that felt it was lacking a sense of renewal convened its second offsite in Silicon Valley, where the team immersed itself in learning about innovation from start-ups and other cutting-edge companies. How frequently these offsites are needed will differ from team to team. But over time, the new behavior will take root, and team members will become aware of team dynamics in their everyday work and address them as required.

In our experience, those who make a concerted effort to build a high-performing team can do so well within a year, even when starting from a low base. The initial assessment of team dynamics at an Australian bank revealed that team members had resorted to avoiding one another as much as possible to avoid confrontation, though unsurprisingly the consequences of the unspoken friction were highly visible. Other employees perceived team members as insecure, sometimes even encouraging a view that their division was under siege. Nine months later, team dynamics were unrecognizable. “We’ve come light years in a matter of months. I can’t imaging going back to the way things were,” was the CEO’s verdict. The biggest difference? “We now speak with one voice.”

Hard as you might try at the outset to compose the best team with the right mix of skills and attitudes, creating an environment in which the team can excel will likely mean changes in composition as the dynamics of the team develop. CEOs and other senior executives may find that some of those they felt were sure bets at the beginning are those who have to go. Other less certain candidates might blossom during the journey.

There is no avoiding the time and energy required to build a high-performing team. Yet our research suggests that executives are five times more productive when working in one than they are in an average one. CEOs and other senior executives should feel reassured, therefore, that the investment will be worth the effort. The business case for building a dream team is strong, and the techniques for building one proven.